The Race to Make Clean Air

I don’t usually say yes to press enquiring about projects. At the beginning of March 2021 I received a call from Reeves Wiedeman a reporter from New York Magazine asking me about Molekule – the air purifier I helped bring to market in 2014.

I’d been introduced to Jaya and Dilip Goswami the Founders and Peter Riering-Czekalla the head of design by my good friend Alexander Baumgardt. Dilip spoke passionately about the technology behind the product which had evolved from an invention by his father, preeminent scientist Yogi Goswami.

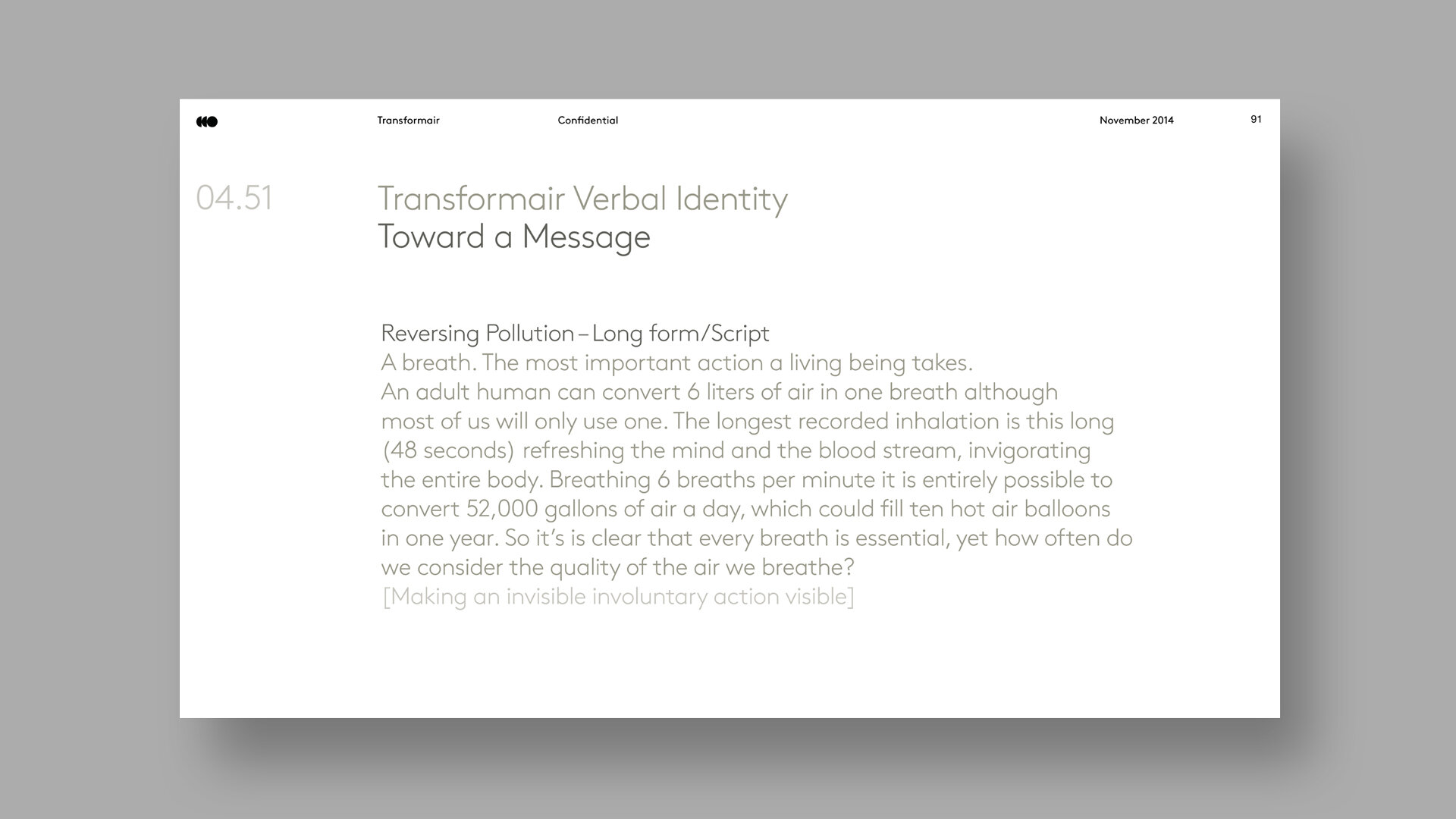

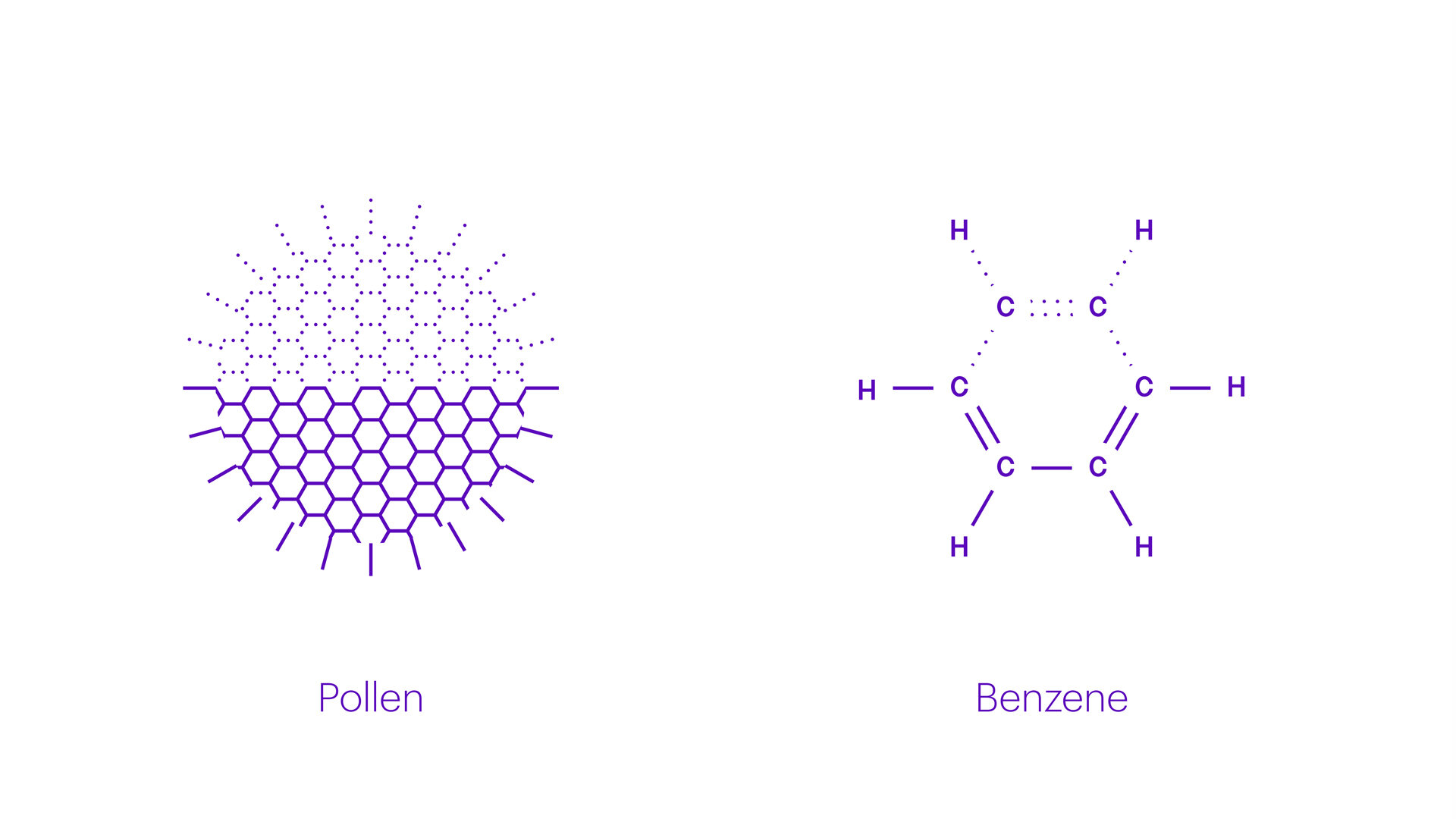

The technology, Photo Electrochemical Oxidation, used a catalyst coated filter which reacted with specific wavelength Ultra Violet light leading to the oxidation of organic matter. Put more succinctly the filter destroyed the filtered particles rather than trapping them.

HEPA filters, the prevailing technology, had been developed by scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project in the 1940’s to deal with radioactive dust. HEPA or “high-efficiency particulate air,” filters are mats of fibers, with tiny gaps of varying microscopic diameters between them which strain out and capture pollutants.

Yogi had discovered the Photo Electrochemical Oxidation process while working on environmental depollution of water. Dilip had asthma as a child and Yogi wondered if PCO technology could be adapted to clean air. He spent years perfecting the process obsessed with the idea that an active filter could create better results than a passive filter like HEPA.

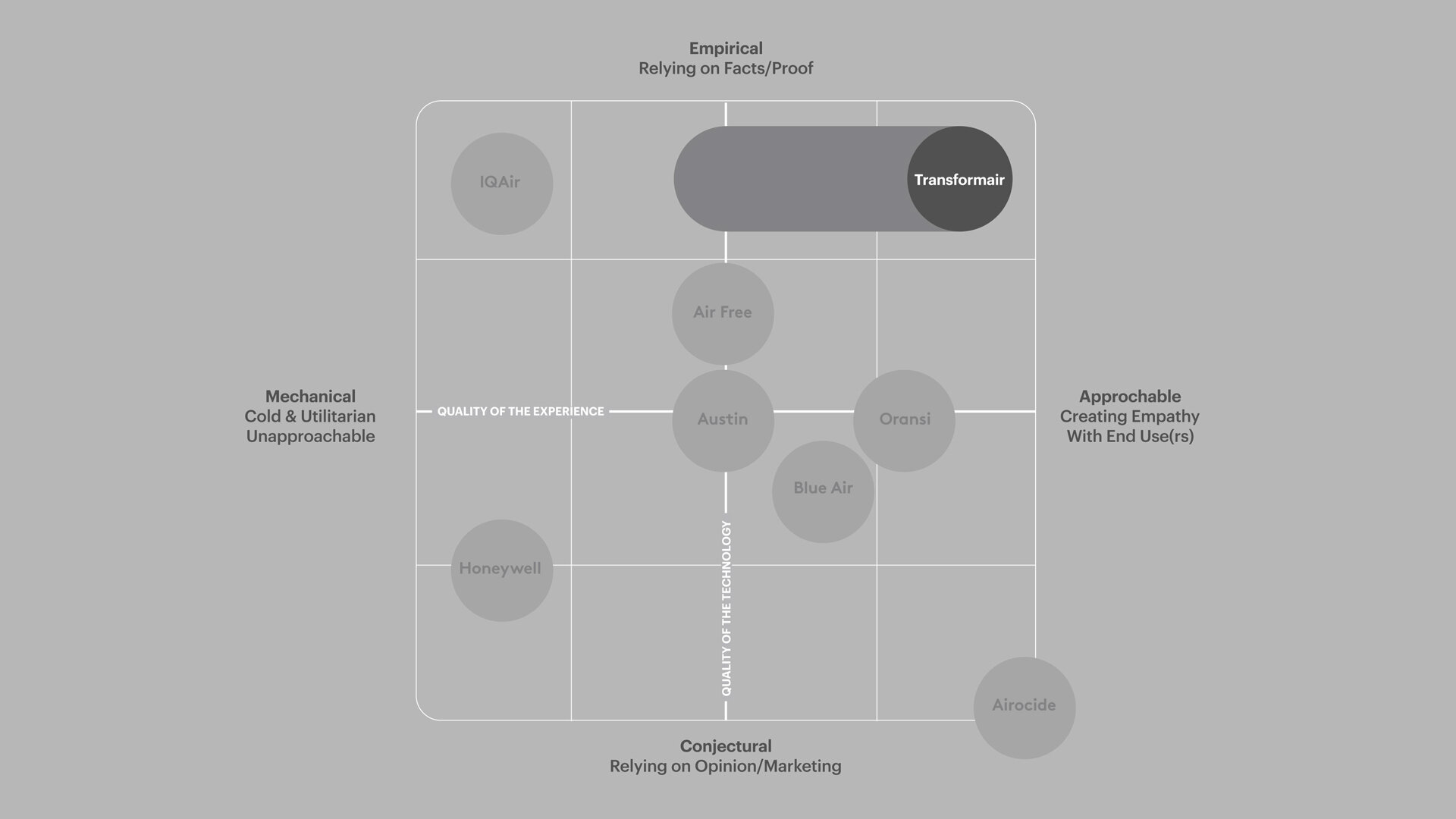

The Molekule product was in early prototype phase and the team needed a way to launch the product in a market which is full of pseudoscience and unqualified claims. Although I advised against it, the founding team were adamant that a scientific approach was at the core of the company.

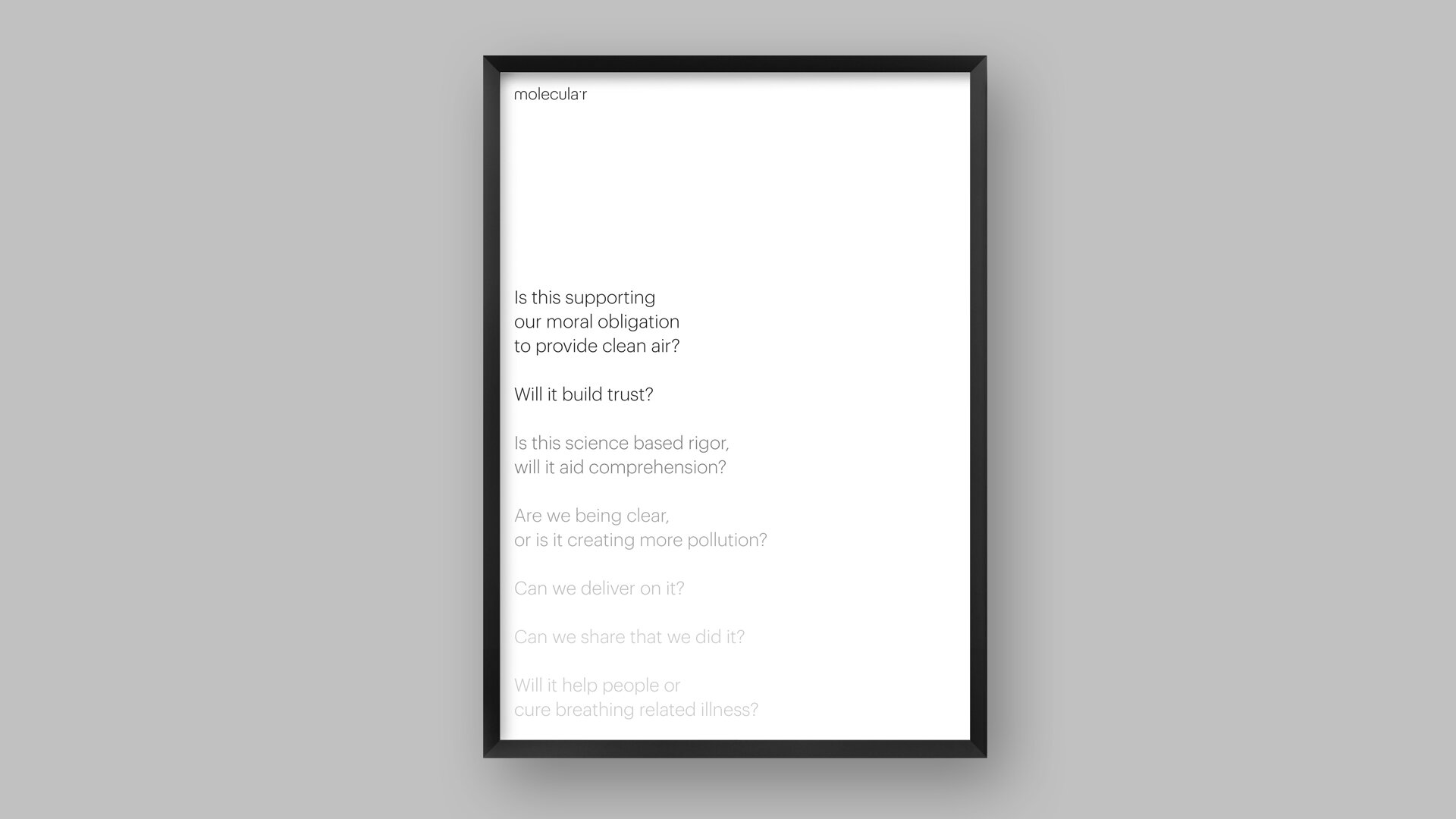

Interestingly, Dilip talked about the product in different way. In our first conversation he’d said that he believed there was a “moral obligation to provide clean air”. This warmth and passion seemed like it was from the other side of the brain to science. And as we evolved the brand, it became clear that the counterbalance between Science and Empathy was the market opportunity. Dilip cared deeply about the people who were suffering like he did and it showed.

In the search for a tone for the brand, it dawned on me that a Good Teacher also believed in empirical fact but always retained the empathy to provide guidance to the student. The Good Teacher became the tone. The shared belief between the company and its customers became ‘A Catalyst for Human Progress’. Dilip’s passion for clean air unified with the normalcy of activity gained by all those who were suffering from air related illness.

The Name of the company we proposed was Molecular. The silent . with the design reflecting the language of the pollutant, also hinting at the outcome air. The design system created by Derek and Joanne was one of the best I’ve seen, I was so proud of their work. Ultimately Peter decided to work with my good friends at Character, choosing the adapted name Molekule.

When Reeves Wiedeman interviewed me, he focused primarily on the naming of the filter. PECO, the name I proposed was an acronym of the process Photo Electro Chemical Oxidation. I proposed this name because like HEPA it contained four letters. It was clear to me that PECO could become a new standard for filtration.

In his published article Mr Wiedeman see’s this naming as a calculated act to undermine HEPA. But as I said to him at the time, proposing a new standard doesn’t destroy the old one, in fact introducing new technology pushes everyone to improve. HEPA is 80 years old, it needs to get better. Clean air is going to continue to be a problem in a world with so much pollution and the category will have to adapt and improve along with the pace of problem.

Much of the article focuses on Molecules failure to compare to the performance of HEPA machines. But Molekule are continuing to invest in PECO technology and have created double digit improvements in the effectiveness of the product. I equated this to the innovation of the incandescent lightbulb – a deeply inefficient product which remained the standard for more than 100 years – but today LED lights use 75% of the energy and last 25 times longer. I could have easily used the combustion engine as another example. Technological innovation takes time. When we’re being critical why wouldn’t we encourage innovation rather than condemn it?

But I don’t take issue with Reeves Wiedeman’s approach, the press form an essential part of the innovation process providing much needed checks and balances. But even though the article tries to paint Molekule as inefficient it fails.

The new standard compares to the old standard, yes, it’s more expensive, and some HEPA machines outperform in the standardized HEPA test. But one fundamental point is missed. Passive filters trap pollution, they don’t destroy it. HEPA filters are the incandescent lightbulb – they work but the world can do better.

Team

Marc Shillum – Strategy, Writing

Paul Valerio – Research

Derek Kim – Senior Designer

Joanne Ong – Designer